Artwork Introduction

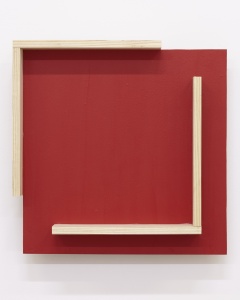

Kishio Suga is a major representative member of the art movement known as Mono-ha which was active in Japan from the end of 1960 until the 1970s. From that time onwards, he has continued to deepen and enrich his contemplation of Mono-ha’s key concerns, resulting in the consistent production of original works. Having studied under Yoshishige Saito at Tama Art University, Suga began to freely manipulate materials such as pieces of wood, stone, metal fragments and plates of glass, sometimes configuring the different materials of his works in conciliatory form, and arranging them in intentional confrontation with one another within the exhibition space. Further, Suga’s practice does not solely give existence to mono (things), but through the act of expressing a mutually dependent relation between mono and ba (place) or mono and mono, the existence of mono itself becomes more prominent, imbued with a kind of ‘relevance’, a ‘difference’, a ‘complexity’ or a ‘composite-ness’ which at the same time serves to reinvigorate the exhibition space.

His use of Kanji in titles expresses his own neologisms, and the indication of his practice as a conceptual artist. However, Suga differs from other conceptual artists in that in his work mono are not merely treated as ‘solid matter’. They are not given their meaning through man’s subjective perspective, but rather they embody a tendency towards a unique theory, a profundity of significance that is only limited by our own reactions. In Suga’s view, mono’s existence is grasped as possessing a certain contemporaneity, or a current-ness, and the role of the artist being to comprehend it and draw it out. Within many of his writings and interviews, Suga uses the expression that mono contains within it a form of potentiality, in relation to which he describes the notion being able to ‘see unseeable things’. In such statements by Suga, we find the embodied significance of skeleton of the concepts presented by his work. Indeed, Suga devotes a large amount of time to this act of ‘seeing’ before arriving at the eventual creation of a particular artwork. In his own words, below:

‘Things which are ‘unseeable’ with the human eye might perhaps also be ‘materials’ […] As to what these visually ‘unseeable’ ‘materials’ might be, first off, the thought and awareness necessary to produce mono might be one.’

(Kishio Suga, “The ‘Multiplicity of Things’”, ‘dialogue – Kishio Suga’, exhibition catalog, Yamaguchi Prefectural Art Museum, 1998)

‘But I realize that if one exceeds only people’s performed consciousness, then conversely the substance of the thing is weekend, I can fill a thing with my thoughts and ideas, but then arriving at the realization that “this is it”, I think it works better to leave it up to the reality of ‘things’ to make the point. This is because in the time it takes to make a thing, the concepts migrate and disappear into it and instead it is the sense of substance of the thing itself that becomes central to the work. ’

(Kishio Suga, Kishio Suga catalog, Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo Gallery, 2006)

In this sense, in accompaniment to the act of directly exerting influence on ‘unseeble’ ‘materials’ to produce artwork, the process by which such materials are transformed into substance is continuously and conscientiously elaborated upon and re-examined by Suga. In this way, the final artwork achieves a high level of purity. Suga’s works have consistently been produced with this unique structure and creation methods for a long period spanning over 45 years. Today, in relation to the significance of Suga’s works, the Chief Curator of the Tokyo Museum of Contemporary Art, Yuko Hasegawa, and the art critic Midori Matsui remark the following:

‘In the change brought about by Suga7s work, everything is part of this constructed world and these elements are all infinitely important and inevitable. However, the original meaning or function of that object or thing has been deconstructed, providing the experiencee of a state in which things or matters afford discovery and perception.

Through Suga’s work we can reaffirm the facr that weare animals, and also recognize how blessed we are that we are so closely connected to out world through the benefits of perception.

That is where the meaning of Suga’s work lies today.’

(Yuko Hasegawa, ‘Thoughts on Kishio Suga’, in Kishio Suga: Situated Latency, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2015)

‘This ability to encourage interaction between people and things enhances the open structure of Suga’s work. His actions or installations do more than simply recognize unique forms of existence pertaining to individual things: by making people see such forms, his invented “things”(mono) mediate human thinking about man’s relation with things and the actuality of living in an immanent world.’

(Midori Matsui, ‘Approaching Kishio Suga : Methods for Capturing an Immanent World’, Kishio Suga catalog, Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo Gallery, 2006)

In the midst of contemporary society’s complex state of affairs, continuously re-iterating and altering at high speed, Suga’s works seem to be trying to extract the structure of a universal kind of world. Taking every measure to avoid the stereotypical idea of “ things or artworks could be understood in symbolistic manner“, Suga’s works apply great variety of approaches to us. Using the materials of the everyday, Suga draws back the veil onto a new world, and as he does so we are set free from the constraints of our regular awareness. Perhaps we are then able to experience a new kind of sight, and a newly activated spirit.

On Mono-ha

Mono-ha was an art movement that prospered during the same period as American Minimalist Art, Italian Arte Povera and so forth. In the art scene from the 1960s to 1970s, in iterations the world over, Mono-ha’s acts of positioning ‘things’ themselves in the place of where they used to only be considered as the suitable materials for art-making, and directing human eyes to perceive ‘things’ themselves became a topic of fascination according to numerous art critics of the time. This idea was introduced in a collective form at the exhibition Japanese Avant-Garde 1910-1970 (Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1986), where it was met with high acclaim internationally. Starting with the 2005 exhibition at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, Mono-ha Reconsidering, followed by the 2012 exhibition at Los Angeles gallery Blum & Poe Requiem for the Sun; the Art of Mono-ha (curated by Mika Yoshitake, Curator at the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington) there have up until today been numerous major exhibitions planned and executed for Mono-ha works. Henceforth, surely Mono-ha will only continue to bask in the world’s attentions even more.

On the Exhibition〉

This exhibition at Tomio Koyama Gallery, following on from one at the gallery’s Hikarie space in March of this year, marks our fifth solo exhibition of Kishio Suga. The exhibited works comprise roughly 10 larger and 20 smaller wall-mounted pieces, and two floor-based works, all of them newly created.

Suga remarks the following about this exhibition:

‘To be able to see a thing is not, in itself, difficult, but to understand the continual states of interiority, the essence of a thing, is generally less straightforward.

Further, the act of expressing something in the form of what is called an ‘artwork’ is not, in itself, difficult. However, for an artwork to be able to be the art work, incorporating the existent evident of the realized singularity or internalizing within oneself its surrounded place or atmosphere is rather difficult.

It is challenging because of the necessity of being able to continue to express, within the perceived atmosphere and the area of the thing (the mono), that there is a kind of ‘intentionality’. Even the human being expressing this cannot achieve anything without some sort of point of reference. Being able to undertake any kind of production is, from both the ‘far side’ of the thing (mono), and from the side more proximal to us of its surrounding atmosphere or environs, one feels that there exists some kind of ‘intentionality’. Not only does it exist, but by means of this ‘intentionality’, perhaps also one is able to perceive another kind of existing thing or liminal domain. So to speak (if there is not this ‘intentionality’), one can see nothing at all.’

– Kishio Suga

The art critic Midori Matsui offers the following further comments regarding Suga’s work:

‘This experiencee indicates that an artificially constructed “thing” could also become a phenomenon, reflecting the fluidity of a phenomenal world. This in turn conveys an unceasing feeling of freedom, when the spectator realize the elusiveness of perception, which escapes the finest archive of knowledge.’

(Midori Matsui, ‘In the Way of Kishio Suga: Mechanism to Capture the Creating World’, Kishio Suga catalog, Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo Gallery, 2006)

Nowadays receiving close scrutiny from art worlds both within Japan and abroad, Suga still continues to investigate, to aim at, and to express the material, substantial reality of mono and its surrounding atmosphere. We look forward to welcome a great many people to view the newly work of this historically significant artist of our time. The latest works remain un-dulled by the passage of time and imbued with a sensation of freedom. We warmly encourage you to seize this opportunity.